Where did we come from?

Poland, situated in the middle of Europe, has had a long and turbulent history. It emerged from the mists of prehistory in 966, when Prince Mieszko accepted catholic faith and married a Czech princess, Dąbrówka.

Thousand years ago, in 1025 Mieszko’s son, Boleslaw “the Brave”, had the distinction of being the first of several crowned Polish kings. The crown, sent by the Pope from the Vatican, was the symbol of Poland’s formal recognition as a member of Western Christendom.

In the 14th century the king Casimir the Great, though the last of the Piast dynasty, was the first king of Poland to lay a permanent legal and institutional foundation for the monarchy. His grand nice, Jadwiga, was crowned as a Queen of Poland in Krakow in 1384. She then married the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Jagiello, and founded the Jagiellonian dynasty, which ruled both Poland and Lithuania for almost two centuries. This arrangement was transformed into a permanent constitutional union in the sixteenth century, when the assembled Polish nobles and Lithuanian princes established a united, but dual states, with separate laws and administration, although jointly governed by an elected King and a common parliament. At the request of the nobility of Ukraine, the southern province of the Grand Duchy was also incorporated into the first Republic of Poland and Lithuania. For over two centuries, it prospered as the largest multicultural state in Europe, with a profusion of peoples, a variety of religions and many languages.

The eighteenth century saw the growth of absolute power in neighbouring countries and a crisis of social, economic and political life in the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Polish Democratic Constitution was passed in Warsaw on the 3rd of May 1791, the first such constitution in Europe and the second in the world. With the intention of saving Poland, it could never be fully introduced. The three consecutive partitions of Poland, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, were caused by the compulsive desire of Russia to crush the Polish reforms. Prussia and Austria acquiesced. Poland of the time of Enlightenment had been oppressed by despotism and disappeared from the map of Europe for over 120 years.

Despite the complete abolishment of essential forms of independence and harsh persecutions after three unsuccessful uprisings, the inhabitants of the former Republic survived its fall and, with them, their culture, languages, religions, social and political attitudes. They formed the living bridge between Poland’s ancient past and the Second Republic of Poland, which emerged anew after the First World War in l918.

Twenty years later, the Second Republic of Poland was invaded by Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia. Poles fought for freedom on both western and eastern fronts during the Second World War and in the occupied homeland. 15% of the Polish population was lost and one third of Polish territory was annexed. Betrayed by US and England in the Yalta Agreement, Poland was subsequently occupied by the Russian communist regime for the next 45 years.

In 1989, thanks to the Solidarity movement, Poland regained her independence and instituted the Third Republic. Over 35 million citizens live within its present borders.

During the last two centuries millions of Poles have escaped the persecution of their homeland, in search of freedom and human dignity. Currently, almost 20 million people of Polish heritage live outside Poland.

First Polish Settlers in Australia

Lech Paszkowski, an authority on history of Australian Polish community, indicated that the first Poles to come into contact with the southern continent were sailors and revellers taking part in exploratory expeditions under foreign flags at the end of the 18th century. Not surprisingly, since the European settlement of the continent began as a penal colony, the first known settler from Poland was also a convict. Joseph Potowski, who had been sentenced for stealing in England, came with Irish wife and children in 1803 to settle in the newly established colony near Melbourne. He helped establish the colony in Hobart, where he eventually died in 1824. Other Poles, political refugees, periodically arrived in New South Wales, Tasmania and Victoria after the November Uprising in Poland in 1830.

The first organised groups of Polish settlers arrived in South Australia between 1844 and 1858. They invited the first Polish priest Fr. Leon Rogalski SJ and build a little church of St. Stanisław Kostka and a school for their children and established a settlement of Polish Hill River near Sevenhill in Clare Valley.

The first organised groups of Polish settlers.

Fr. Leon Rogalski SJ

Church of St. Stanisław Kostka

The First Poles in Australia

The best-known Pole to enter the pages of Australian history was Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki.

He named the highest mountain of the Australian continent after the internationally applauded Polish freedom fighter and hero, general Tadeusz Kosciuszko. Several of other regions, rivers and significant sights bear Strzelecki’s name, in Victoria, Tasmania and NSW. He located deposits of coal, iron, pyrites, copper, lead, oxides of titanium, opals, agates, asbestos, marble, kaolin and other minerals. Strzelecki was versed in topography, mineralogy, geology, agricultural and analytical chemistry and cartography, bringing all his extraordinary gifts to bear on the new frontier of Australia over four tireless years. He worked hard to unravel the scientific problems of his time and to describe a strange continent. It is astounding to chart the extent of Strzelecki’s travels, mostly on foot, throughout the Australian mainland and Tasmania. Most of his walking was on the first primitive tracks of the colonies though some, like his ascent of “Mount Kosciuszko” and through Gippsland, broke new ground. He pleaded for the preservation of the Aboriginal race and culture, but his passionate defence of the “noble savage” was isolated and ignored.

Many other Polish migrants have been contributing to the development of Australia since the earliest pioneering days. For example:

Leopold Kabat (1830-1884) – Superintendent of the Victorian Police

Władysław Kossak (1828-1918) – Inspector of the Victoria Mounted Police

Emeryk Boberski (1830-1924) – Mayor of Ararat and local businessman

Franciszek Ksawery Górski – (1828 – 1868) – made a fortune in Melbourne as a marchat. Returned to Poland in 1863 to take part in uprising and fight agaist Russia

Major Severin Korzelinski (1804-1876) – Author of “Memoirs of Gold-Digging in Australia”

Gracius Broinowski (1837-1913) – ornithologist and painter, author of the monumental publication: “Birds of Australia”

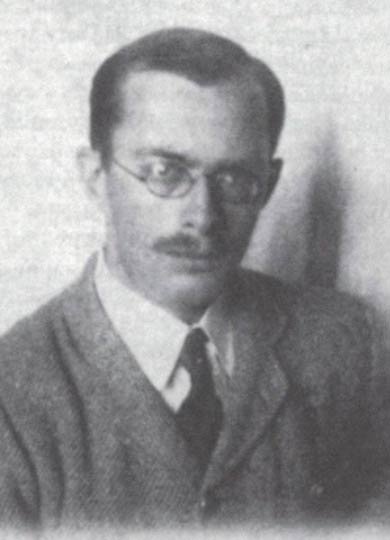

Stanislaw de Tarczynski (1882-1952) – The Symphony Orchestra concertmaster for the ABC and J.C. – Williamson Opera Company

Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) – Famous anthropologist

Rev. Leon Scharmach (1896-1964) – The first Polish bishop consecrated on Australian Territory

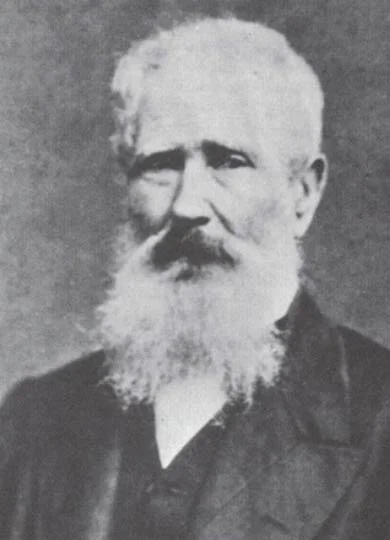

Seweryn Rakowski (1810-1887) – former officer, succesful businessman in Melbourne. With his involvement on the 30th of November l863 the Committee and Trustees of the “Polish Fund to aid the struggle of Poland for Independence” - was established in Melbourne.

There were many other 19th century Polish settlers recognised as successful Australians.

Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki

Major Severin Korzelinski

Gracius Broinowski

Stanislaw de Tarczynski

Bronislaw Malinowski

Rev. Leon Scharmach

Seweryn Rakowski

Władysław Kossak

Leopold Kabat

Franciszek Ksawery Górski

Emeryk Boberski

Post-War Migration

There were not many Polish migrants in Australia prior to the end of World War II. The first to arrive after the War were ex-soldiers who served in the Polish Forces under British Command and, leading them, were Polish Rats of Tobruk and airmen who fought alongside the Australians. The comradeship of the Australian and Polish forces during World War II was well known and documented.

Poland was the first to confront Hitler’s military machine. By the end of the war, it had raised a regular army of nearly 600 000 beyond its borders. Including the soldiers of the underground army in the occupied Poland, the Polish nation had an army of over one million and, as such, was the fourth largest contributor to the victory of the anti-Nazi coalition. The Polish ex-servicemen march with pride in the annual ANZAC parades all over Australia.

Political Character Of Polish Migration

Following the implementation of Arthur Calwell’s immigration programme in 1948, a massive Polish immigration from “Displaced Persons” camps in Europe began. The majority were young, single and childless couples. Later came families, and widows with small children from Africa, Lebanon and India. Over 70 thousand of them settled in Australia.

Though feeling betrayed by the Allies, these Poles were forced to leave their homeland and build a new and happy “home” in Australia, but they could not stop thinking of and praying for the freedom of their beloved homeland.

Most National Days became important anniversaries that were fervently celebrated each year, for a peaceful means to end the oppression in Poland. 1980 marked the 40th anniversary of “Katyń”, a terrible crime symbolising the many mass graves of Polish officers, public servants and intellectuals massacred by Stalin’s communist regime. They numbered 25,000.

The brutal introduction of martial law on the 13th of December 1981 in Poland and the detention of members of the free trade union “Solidarity”, sparked widespread protests around the world. In Australia also, the Polish Community and other ethnic groups, as well as the leaders of the Liberal and Labour parties joined together to raise their voices against the Soviet tyranny. That essential relief could be sent to Poland, Malcolm Fraser’s Commonwealth Government offered one million dollars, while the Polish Community, through an appeal called “Help Poland Live”, collected another million dollars. As the result of the brutal crushing of the “Solidarity” movement in Poland, many thousands of young Poles escaped persecutions to seek freedom abroad. Some 30 thousand of them settled in Australia.

Some Statistics

Data from the 2021 Census of population and housing shows that in Australia 209,281 persons are of Polish ancestry.

62,570 people in Victoria claim to have Polish ancestry, but only 13,670 of them speak Polish at home. Over 40% of Poles in Victoria have obtained a tertiary education. Almost 50% are Catholic, over 10% are of Jewish traditions, almost 10% belong to the other Christian and non-Christian denominations and over 30% have no religion or did not state their affiliation to any religion. Over 97% have accepted Australian citizenship. The great majority of Poles own their own homes. Over 80% live in grater Melbourne and the rest of them in Geelong, Ballarat, Gippsland and in all other regions of Victoria.